The emergence of big data policing

The Emergence of Big Data Policing

Sarah Brayne

Introduction

The past decade has seen both the proliferation of surveillance in everyday life and the rise of “big data.” Analysis of this big data has expanded into finance, health, social science, sports, marketing, security, and criminal justice. Focusing on the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD), this brief explores whether and how adopting big data analytics transforms police surveillance practices. Big data analytics have the potential to reduce bias, increase efficiency, and improve prediction accuracy. However, they also have the potential—through predictive algorithms and other means—to reinforce bias and deepen existing patterns of inequality.

Being at the forefront of data analytics makes the LAPD an important site for this research. Therefore, its practices may forecast broader trends that could play out in other law enforcement agencies in the coming years.

This brief is based on fieldwork conducted between March 2013 and August 2015 with the LAPD, the Los Angeles County Sherriff’s Department, other regional and federal agencies, as well as at surveillance industry conferences and with individuals working at technology firms that design analytic platforms used by the LAPD.1 Using interviews with 75 police officers, detectives, civilian employees, surveillance technology employees, and others, in addition to observations of data analysts, ride-alongs in police cars, and archival research of surveillance industry literature, this research demonstrates that, in some cases, the adoption of big data analytics is associated with mere amplifications in prior practices, but in others, it is associated with fundamental transformations in surveillance activities.

Key Findings

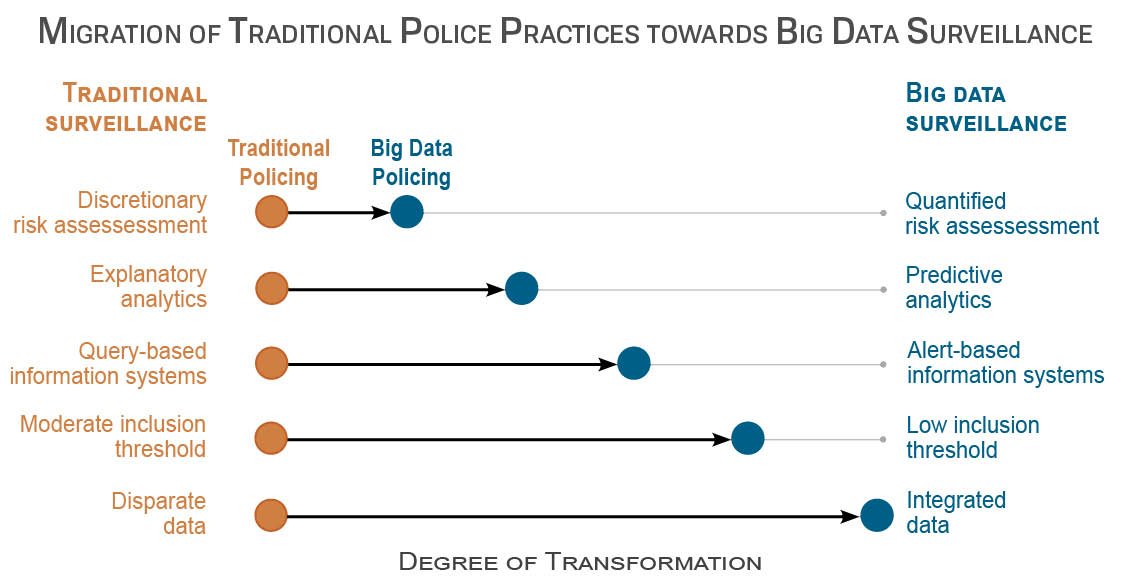

The adoption of big data analytics has shifted traditional police surveillance practice in five key ways. Listed from the lowest to the highest degree of transformation between traditional policing and big data policing (see figure), they are as follows:

(1) Officers’ discretionary assessments of criminal risk are supplemented with quantified risk scores.

- Risk scores are created by assigning points for a violent criminal history, known gang affiliation, prior arrests with a handgun, parole or probation status, and being stopped by the police.

- People with high point values are more likely to be stopped by police, leading to ever higher point values.

(2) Data are increasingly used for predictive—rather than reactive or explanatory—purposes.

- Rather than simply “chasing the radio” to respond to reports of crimes, the LAPD uses software designed with a proprietary algorithm that purports to predict where future crime is most likely to occur.

(3) The proliferation of automated alerts makes it possible to passively surveil an unprecedentedly large number of people.

- Police no longer have to rely solely on query-based searches in which law enforcement submit requests for information, such as running a license plate during a traffic stop.

- With big data, police can receive real-time alerts when certain variables are present in the data. For example, officers can be automatically notified of warrants or events involving specific individuals, addresses, or cars. Prior to automated alerts, law enforcement would only know an individual’s real-time location if they were conducting one-on-one surveillance, received a tip, or encountered them in person.

(4) There is increasingly a low threshold for people’s information to be entered into police databases which leads to an expansion of surveillance.

- New data collection sensors, such as automatic license plate readers, result in datasets that now include information on individuals who have not had any direct police contact.

(5) Previously separate data systems are merged into relational systems to include data originally collected in other, non-criminal-justice institutions.

- Information collected by other institutions include data from repossession and collections agencies, social media, and electronic toll pass data, and address and usage information from utility bills.

- This data integration represents the largest transformation between traditional policing and big data policing: the creep of criminal justice surveillance into other, non-criminal justice institutions.

This caption describes the image above.

This figure shows the ways in which big data is transforming different aspects of policing. The way big data changes risk assessments of individuals constitutes the lowest degree of transformation. Police now being able to access privately-collected data and data collected by other government agencies represents the largest change between traditional policing and big data policing.

Policy Implications

Big data and algorithmic decision-making are important tools being used to increase efficiency and accountability in a wide range of organizations. Although it holds great potential, big data is not a panacea. On the one hand, big data analytics may be a means by which to ameliorate persistent inequalities in policing. Data can be marshaled to replace undifferentiated suspicion and human exaggeration of patterns with less biased perceptions of risk. As digital trails are susceptible to oversight, it may also be used to “police the police,” ultimately providing an opportunity to increase transparency and accountability. On the other hand, big data policing has the potential to technologically reinforce bias and deepen existing patterns of inequality in at least three ways: by deepening the surveillance of individuals already under suspicion; by widening the criminal justice dragnet unequally; and leading people to avoid institutions—such as medical and financial institutions—that are fundamental to social integration.2

Technological tools for surveillance are far outpacing legal and regulatory responses to the new surveillant landscape. Rather than traditional one-off interactions between police and civilians, new police technologies mean that policing is increasingly broad, automated, and programmatic. Therefore, principles of criminal law and procedure, constitutional law, privacy law, and regulations need to be revisited in order to reflect new police strategies, facilitate accountability, and protect the rights of citizens in the age of big data.

References

[1] Brayne, S. (2017). Big data surveillance: The case of policing. American Sociological Review82(5).

[2] Brayne, S. (2014). Surveillance and system avoidance: Criminal justice contact and institutional attachment. American Sociological Review 79(3), 367-391.

Suggested Citation

Brayne, S. (2017). The emergence of big data policing. PRC Research Brief2(11). DOI: https://doi.org/10.15781/T2JM23X7Q.

About the Author

Sarah Brayne (sbrayne@.utexas.edu) is an assistant professor of sociology and a faculty research associate in the Population Research Center, The University of Texas at Austin.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Horowitz Foundation for Social Policy. Infrastructural support was provided by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (5 R24 HD042849) to the Population Research Center, University of Texas at Austin.