How Is Gestational Weight Gain Linked to Health among Black and Dominican Women 17 Years after Giving Birth?

How Is Gestational Weight Gain Linked to Health among Black and Dominican Women 17 Years after Giving Birth?

Marcela R. Abrego, Andrew G. Rundle, Saralyn F. Foster, Daniel A. Powers, Lori A. Hoepner, Eliza W. Kinsey, Frederica P. Perera, Elizabeth M. Widen

Key Findings

-

Most women in the study (60%) gained more weight than recommended during pregnancy.

-

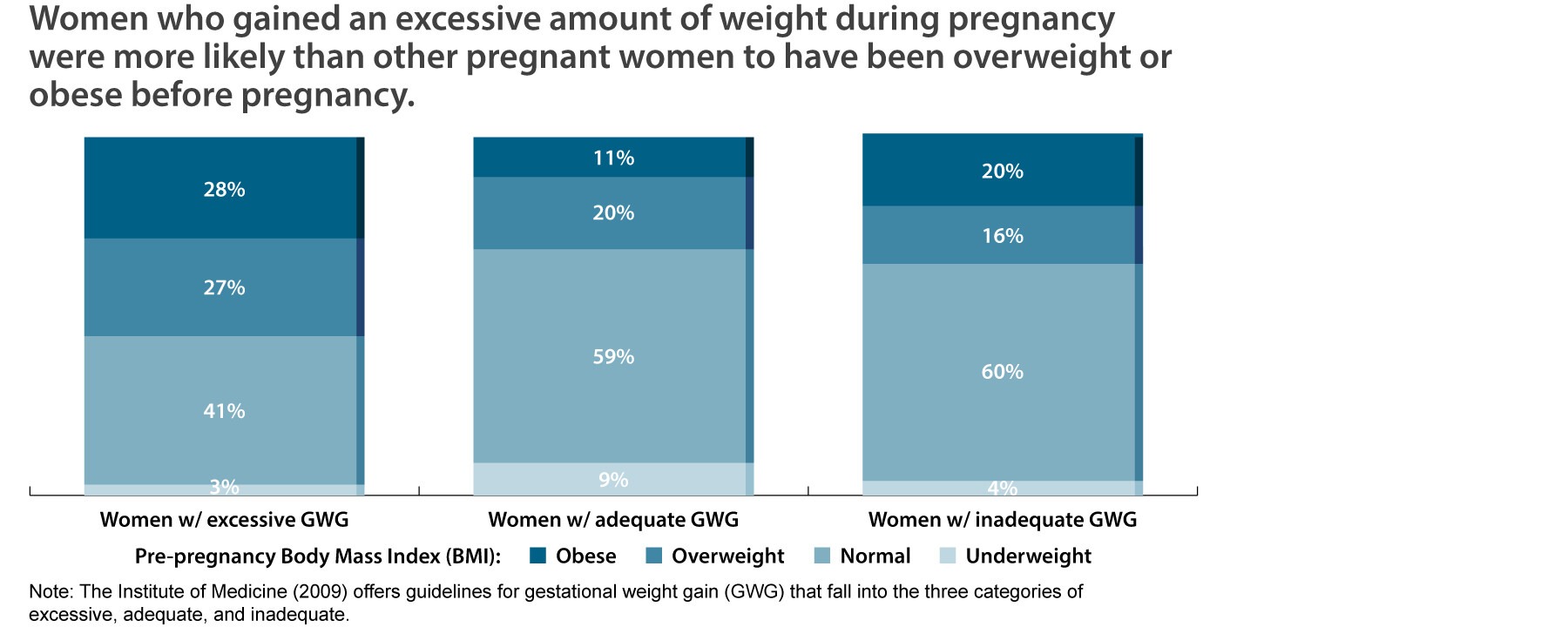

Women who gained an excessive amount of weight during pregnancy were more likely than other pregnant women to have overweight or obesity before becoming pregnant.

-

Excessive weight gain during pregnancy was linked to higher body fat, larger waist size, and more weight kept on 17 years after giving birth.

-

Excessive weight gain during pregnancy was not linked to higher blood pressure or hypertension in midlife.

Most women in the study gained more weight than recommended during pregnancy. Among the 210 women studied, 60% gained more than the 2009 guidelines set by the Institute of Medicine. Looking at gestational weight gain by body mass index (BMI), 5% who were considered underweight before pregnancy gained excessive weight during pregnancy, compared to 50% with normal weight, 24% with overweight, and 20% with obesity. The finding that a higher percentage of women with normal BMI before pregnancy gained excessive weight compared to women with overweight or obesity before pregnancy is different from other studies.

Women who gained an excessive amount during pregnancy were more likely than other pregnant women to have overweight or obesity before becoming pregnant. Among women who gained excessive weight during pregnancy, 55% had overweight or obesity before becoming pregnant. On the other hand, among women with inadequate weight gain during pregnancy, 36% had overweight or obesity before pregnancy (see figure).

Excessive weight gain during pregnancy was linked to higher body fat, larger waist size, and more weight kept on 17 years after giving birth. Seventeen years after giving birth, women who gained more weight than recommended during pregnancy had more fat overall, more weight retained from pregnancy, and larger waistlines. On average, they had 6 kilograms (about 13 pounds) more weight than before pregnancy and waistlines about 5 centimeters (2 inches) larger.

Excessive weight gain during pregnancy was not linked to higher blood pressure in midlife. Despite concerns about long-term heart health, the study did not find a connection between gaining more weight than recommended during pregnancy and having high blood pressure 17 years later.

Note: The Institute of Medicine (2009) offers guidelines for gestational weight gain (GWG) that fall into the three categories of excessive, adequate, and inadequate.

Policy implications

This research shows that gaining more weight than recommended during pregnancy can have lasting health effects that stretch well into midlife. It highlights the need for better education and support for women, especially in communities of color and those with low incomes, about healthy weight gain during pregnancy.

Health policies and practices should help pregnant women meet recommended targets for weight gain. Healthcare providers and community health programs can offer more tailored guidance and engage in postpartum follow-up care that addresses healthy weight, nutrition, and exercise. Providing support and information to women to help them maintain a healthy weight during pregnancy can reduce the long-term risks of obesity and chronic illness and improve health outcomes for mothers and their families.

Data and Methods

The authors calculated gestational weight gain among Black and Dominican women aged 18 to 35 years from a prospective birth cohort. The women in the study were originally part of a health project at the Columbia Children’s Center and lived in New York City (northern Manhattan and the South Bronx). The final sample size was 210. None of the participants had any major health issues during pregnancy and gave birth between 1998 and 2006.

Researchers used medical records, physical exams, and questionnaires to track weight and health outcomes nearly two decades later. They measured weight, height, waist circumference, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, fat mass, and fat-free mass in these women 17 years after giving birth to a baby. The authors used linear and logistic regression to estimate associations between gestational weight gain and long-term postpartum outcomes, adjusting for covariates.

Reference

[1] Abrego, M.R., Rundle A.G., Foster S.F., et al. (2025). Gestational weight gain, cardiometabolic health, and long-term weight retention at 17 years post delivery. Obesity 33(7). https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/oby.24276

Suggested Citation

Abrego, M.R., Rundle A.G., Foster S.F., et al. (2025). How Is gestational weight gain linked to health among Black and Dominican women 17 years after giving birth? Population Research Center Research Brief 10(7). https://doi.org/10.26153/tsw/61102

About the Authors

Marcela R. Abrego, mrabrego@utexas.edu, is a graduate student in the Department of Nutritional Sciences, The University of Texas at Austin; Andrew G. Rundle is professor of epidemiology at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health; Saralyn F. Foster is a graduate student in the Department of Nutritional Sciences, UT Austin; Daniel A. Powers is professor of Sociology and a faculty scholar at the Population Research Center, UT Austin; Lori A. Hoepner is assistant professor in the Department of Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences at State University of New York; Eliza W. Kinsey is assistant professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Pennsylvania; Frederica P. Perera is professor emerita in the Department of Environmental Health Sciences, Columbia University; and Elizabeth M. Widen is associate professor in the Department of Nutritional Sciences, College of Natural Sciences and a faculty scholar at the Population Research Center, UT Austin.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P2CHD042849), awarded to the Population Research Center at UT Austin; grants (T32DK007559, T32DK091227) from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; grants (P01ES09600/ R82702701, P01ES09600/RD832141, P01ES09600/RD834509, P50ES009600) from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences; US Environmental Protection Agency; a grant (UG3OD023290) from the National Institutes of Health Office of the Director; and a grant (RR00645) from the Institute for Clinical and Translational Research.